Tribal Child Welfare Funding Findings

Overview of Funding for Tribal Child Welfare

This section provides some background for how tribal child welfare programs are funded in order to understand the historical context in which these programs operate. The findings from the needs assessment regarding funding are described in the Findings section below.

The federal government is responsible for assisting tribes in meeting the service needs of citizens, through what is called “federal trust responsibility.” Funding for tribal child welfare programs comes from a variety of federal, state, and local sources, including the BIA through the ICWA and Services to Children and Elderly Families, grants to tribal courts, and HHS-administered funding through Title IV-B (Subpart 1, Child Welfare Services and Subpart 2, Promoting Safe and Stable Families) and Title IV-E Foster Care.

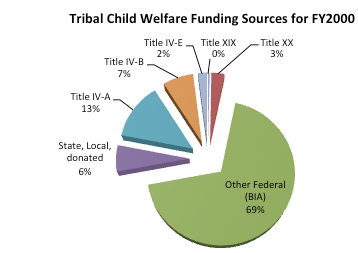

A 2004 study of selected tribal child welfare programs found that the majority of funding for fiscal year 2000 came from BIA-administered funding (just under 70%) while HHS-administered funding only accounted for 25%, with 2% from Title IV-E and 7% from Title IV-B. Figure 1 below shows the complete funding distribution from this study.

Figure 1. FY2000 distribution of tribal child welfare funding sources (n= 38)

Although this study focused on a relatively small sample, anecdotal evidence from field practitioners supports the conclusion that the BIA provides the majority of funding for tribal child welfare programs, with some indications of a growth in funding through tribally generated revenue. The BIA administers several different funding sources for tribal child welfare programs. Table 1 shows these various sources, and is from page 6 of the same report (see n. 3).

Table 1. Child Welfare Funding Sources Administered by the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs

|

Source |

Purpose |

Funding/Disbursement |

FY01 Funding |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indian Child Welfare Act |

Operate tribal programs in order to determine and provide placement for tribal children. Funds may be used for staff support and administration. |

Funds provided annually to federally recognized tribes. Funding determined through a joint tribal/federal process that takes into account need and historical funding levels. |

$26,449 to $750,000. Average of $60,000 per tribe. |

|

Services to Children, Elderly, and Families |

Administer social services programs for adults and children, and support caseworkers and counselors. Support tribal substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. |

Funds provided annually to federally recognized tribes. Funding determined through a joint tribal/federal process that takes into account need and historical funding levels. |

$10,000 to $4,800,000. Average of $100,000 per tribe. |

|

Indian Social Services Welfare Assistance |

Financial assistance for the basic needs of eligible Indians living on or near reservations. Also reimburses cost of foster home/institutional care for dependent, abused/neglected, and disabled Indian children. |

Funds provided directly to income-eligible Indian members living on or near reservations and to federally recognized tribes for the care of children in need of protection. Funding determined through a joint federal/tribal process based on need. |

Few hundred to several hundred dollars monthly per individual. |

|

Grants to Tribal Courts |

Operate judicial branches of government. |

Funds provided annually to federally recognized tribes with the demonstrated capacity to administer a tribal court. Funding determined through a joint tribal/federal process that takes into account need and historical funding levels. |

Information not available. |

Title IV-B and Title IV-E Funding

The HHS administers funding through the Title IV-B and Title IV-E grants, which represent a small but very significant portion of funding for tribal child abuse and neglect activities. This section presents a brief overview of Title IV-B and Title IV-E funding that supports programs and provides important context to understanding the findings related to tribal child welfare programming needs learned through this assessment.

Prior to the passage of the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-351), tribes were not eligible to access funds from the Title IV-E Foster Care and Adoption Assistance Program in order to provide services to American Indian/Alaska Native children, except through a cooperative agreement with their state. Therefore, “tribes [had to] depend on the states’ willingness to pass along federal funding, and that willingness varies from state to state” (North American Council on Adoptable Children 2007). The newly enacted Fostering Connections Act now allows tribes to choose to access Title IV-E funds directly from the federal government in order to administer their own foster care programs, as well as the option of administering kinship guardianship assistance and adoption assistance programs, and provides additional impetus to states to negotiate tribal/state IV-E agreements, for those tribes that may prefer this option.

Federal Title IV-B has two subparts. Subpart 1 is a discretionary grant program available to states and tribes for programs that promote the safety, permanency, and well-being of children in foster care and adoptive families. As of 2009, 148 of the 565 federally recognized tribes were accessing Title IV-B funding (26%). Tribes must be federally recognized in order to be eligible to receive Title IV-B funding. Title IV-B funded tribes and Title IV-E developmental grantees can receive T/TA and Title IV-E planning grants (described below) from the CB.

Subpart 2 funds can be used to support services for family preservation, family support, time-limited reunification, and adoption promotion and support. In order to receive T/TA, tribes must be eligible for and receiving Title IV-B funding; in order to receive funding, tribes must have an approved Title IV-B plan. Title IV-B funds are allotted to tribes based on the number of children under the age of 21 as reflected in U.S. Census Bureau data, unless a tribe has certified an alternative number that has been approved by the ACF.

Title IV-E is an open-ended entitlement program that requires a federally approved Title IV-E plan for participating states and tribes. It provides partial federal reimbursement for foster care payments, adoption assistance payments, kinship guardianship payments, and related administration and training costs. Title IV-E funding requires the state or tribe to provide matching funds for Title IV-E–eligible services.

Title IV-E funding has been available directly to states since the early 1980s but only available indirectly to tribes through tribal/state agreements. As of 2008, there were approximately 90 tribes with tribal/state agreements, and 70 of these allowed for either one of a combination of maintenance, administrative, or training activities funded by Title IV-E. Title IV-B and Title IV-E have an interrelatedness that requires Title IV-B, Subpart 1, funding access prior to directly accessing Title IV-E funding.

The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (PL 110-351) allows for direct Title IV-E funding to eligibletribes for foster care, adoption assistance, guardianship placements, and independent living services. Currently, tribes may apply for a one-time grant in order to assist in the development of an approved tribal IV-E plan. Seven tribes received the initial federal planning grants to develop a direct Title IV-E plan in the fall of 2009. Four more tribes received these grants in the fall of 2010.

Title IV-E is a program funded to cover a limited scope. However, the various provisions of Title IV-B, Subpart 1, and Title IV-E require that the Title IV-E agency (state or tribe) provides a continuum of child welfare services that ranges from helping to prevent child abuse and neglect; responding to and investigating allegations of abuse/neglect; providing intervention and treatment services to prevent a child's removal from home or providing temporary foster care if removal is necessary; helping families reunite or helping children and youth achieve other permanency goals such as adoption, guardianship, and living with a relative; and providing post-permanency support (U.S. DHHS, ACF, CB, 2009a).

In Title IV-E, there are numerous provisions that require a state or tribe to consider how children can be kept safe. Background check requirements for prospective foster and adoptive parents or guardians are one means. Several additional requirements for ensuring child safety with which a state or tribal child welfare program must comply include

-

Checking any child abuse and neglect registry maintained by a State/Indian Tribe in which the adults living in the home of a prospective foster or adoptive parent have resided in the preceding five years;

-

Developing case plans, with parental involvement, within 60 days of a child entering foster care;

-

Operating an information system from which can be readily determined the status, demographic characteristics, location, and goals for the placement of every child who is, or within the preceding 12 months was, in foster care;

-

Reporting semi-annually to ACF information about each child in foster care as well as each child adopted during the reporting period, through the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS); and

- Establishing a tribal authority responsible for developing and maintaining tribal licensing or approval standards for tribal foster family homes and child care institutions (U.S. DHHS, ACF, CB, 2009a).

Background about Tribal Communities

This section provides background information about how tribal communities are structured so that the needs assessment findings (presented in the Findings section below) can be understood in the context of tribal program organization.

According to the BIA Web site, as of December 2010 there were 565 federally recognized tribes in the United States with a population of about 1.9 million American Indians and Alaskan Natives. This tribal population is spread throughout the United States in communities varying in geographic size, location, values, traditions, and cultural norms.

Tribal governmental structures vary from tribe to tribe; many were established by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. A common hallmark of tribal governmental structures is a parliamentary style of decision making that is often quite different from most tribes’ traditional leadership style prior to contact. The following are several examples of common tribal governance structures:

-

An elected 9 member tribal council whose membership includes a chairperson, vice-chairperson, secretary, and treasurer. Tribal programs include social services, environment, education, and health.

-

A 12 member tribal council, plus 5 tribal administrative officers who are appointed through a traditional, cultural leadership process. Tribal programs include, among others, behavioral health, ICWA, housing, and education.

-

External matters are governed by a chairman, vice-president, and 4 council members. Villages remain quasi-independent. One village adopted a Western form of government, while the remaining villages adhere to a traditional form of government. Through the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (Public Law 638), the tribe contracts with the BIA to administer key programs and services.

- An 8 member tribal council whose membership includes a chairperson, vice-chairperson, secretary, and treasurer. Government branches include social services, education, health center, parks and wildlife, credit and finance, transportation, land management, law enforcement, and a tribal court. The tribe also has a PL 638 contract with the BIA and the Indian Health Service for various governmental programs.

Although some of the challenges confronting tribal communities in rural and urban areas are similar to those found in other communities across the United States, tribes may also face unique challenges related to geography and climate difficulties in accessing resources because of lack of transportation; jurisdictional uncertainties; historically strained relations with the surrounding counties; and/or social, health, and economic challenges, including high unemployment rates and high rates of health conditions (i.e., diabetes and alcoholism). Many tribes are located in areas where a tribal child welfare case manager must drive an hour or more just to reach a family’s home. Families, too, must travel great distances to access needed services such as mental health care, substance abuse treatment, or medical services for a child with special needs. Tribes and tribal people must also contend with cultural differences and non-Indians’ unfamiliarity with cultural practices.

Climate and housing also impact the lives of members of some tribal communities. For tribes located in the northern regions of the United States and Alaska, roads are often closed or impassable for days at a time due to inclement weather, and ready access to the community is possible only during certain seasons. Severe housing shortages also provide their own unique challenges in the provision of child welfare services in tribal communities. It is not uncommon to find members of several related families living in a 2 or 3 bedroom home. Often these dwellings are clustered together in a housing area with 75-100 inhabitants, who together may own only 3 or 4 vehicles that are in working condition. Community members rely on these automobiles in order to obtain basic survival items such as groceries, clothing, and water. In turn, someone with a car may not be readily available to transport another person to a meeting with a child welfare worker or to an appointment in a town a considerable distance away. Multifamily housing environments also impact the ability of tribal child welfare programs to license foster and kinship families to provide care for children. Because household members over the age of 18 must pass a criminal background check, the failure of any person living in the home to meet this requirement typically prevents a child from being placed in the home.

Some of the strengths exhibited by tribal communities include cohesive and supportive extended-family systems; intricate social and ceremonial systems that rely on and value community members; strong spiritual and religious institutions; versatility in adapting to changing circumstances; and strong ethical expectations including respect for elders and children.